By Celeste Williams

Some 40 years ago in Indianapolis, when disco dancing and aerobics drew bigger

crowds than Robert Bly and Etheridge Knight, Jim Powell conceived and breathed life into “one special non-profit organization” dedicated to writers and writing — the Indiana Writers’ Center.

While there has been evolution since 1979, including the deletion of a strategic

apostrophe, it is impossible to separate the organization from James Edward Powell. Powell, who turns 69 on February 19, is retired from more than 40 years of teaching, including two decades of nurturing the first half of the IWC. He is ready to celebrate his own major literary milestone: the publication of a book of more than a dozen fiction stories: Only Witness.

The IWC, which is publishing the book of short stories, will combine the launch of

Powell’s new volume and his role in the founding of the Indiana Writers Center at a reception and fundraiser March 8 at the Circle City Industrial Complex.

“Given his lifelong support of Indiana writers, it seems fitting for the IWC to publish his first collection of stories as part of the celebration of our 40th anniversary,” said Barbara Shoup, executive director of the IWC.

It is fitting, too, that the IWC pay homage to its creator. In writing.

——

Powell is seated in the front room of his Broad Ripple home, a laptop atop a stack of books on a coffee table. A clear oxygen line rests near his hip and snakes around the corner out of sight. He mostly ignores it, though the lifeline is close enough to grab if need be.

One can tell he’d much rather ignore the COPD that has constricted his breath and landed him in the hospital for more days than he’d like to count. He occasionally slips a monitor on a finger to check his oxygen level.

The percentage is high. Good.

“I’ve had a horrible health year,” he says. “This past year has been 16 days in the hospital three different times altogether. But that’s the disease,” he says with a resigned shrug.

“I still enjoy things,” he assures with a smile and a clear, steady gaze beneath a shock of white hair. He says illness might have cut short hobbies like gardening, biking and extended Mexico vacations, but not has not turned off his mind. And, Powell insists, he continues to “hear the voices of fiction” in his head: “They keep trying to get out!”

Powell says that image “stems from the many calls I’d take at the Writers Center from people telling me they had ‘a book in my head.’” His reply: “That must hurt; better get it out!”

Powell’s “head-book” has gotten out.

Only Witness includes several stories he has had published in magazines, and a number of newer ones. Its pending publication sends a smile spreading across his goateed face. He says he looks forward to the cover — an “infinity view” concept of a wide, verdant vista melding into endless sky.

Intellectuals & Liars

Powell’s view of the past stretches back to a childhood in tiny Elwood, Indiana, a place he describes as an unlikely “literary capital of Indiana,” the home of poet Jared Carter, a couple of lesser-known authors, and of course, former presidential candidate, Wendell Willkie.

The Willkie High School graduate said he won a writing contest in 6th grade, with a story called “ ‘Xeo’s Long Journey,’ a trip through the Egyptian city of the dead. I wrote a book of poetry in high school. But I never viewed writing as a career. I wanted to be an architect.”

Elwood is a “good place to be from,” he says with a chuckle, noting that leaving the little town was likely a forgone conclusion.

Powell majored in political science at Purdue —urban studies, of all things for a kid from rural Indiana. “But writing was always there, and my imagination was always there, too, so that was good.”

When Powell soured of politics during the Vietnam War, the writing instincts were at the ready as a replacement. “I went to George Washington University for two years, then I just got burned out on politics, because there was anti-war every second of your life. I worked at the Smithsonian for five or six months, came back to Purdue, wanted to change majors but couldn’t graduate if I did, so I graduated poly sci.

“But I started taking literature classes and creative writing classes.”

Powell says Italian-American fiction writer, Arturo Vivante, was a visiting professor at Purdue “who was very encouraging — too much so, perhaps, because I was pretty bad.”

Powell says he had a problem with an essential ingredient of storytelling: plot. “I didn’t know what plot was.”

He says Vivante sent one of his stories to the New Yorker. The rejection letter said something like, “ ‘This piece has problems with the narrative flow.’ Basically they were saying it had no plot!”

Still, he persisted. Powell received an MFA from Bowling Green in Ohio in 1976, then followed his literary interests to California. In 1977, he and a couple of friends started a bookstore in Santa Monica.

The store, “Intellectuals and Liars,” mere blocks from the Pacific Ocean, was a dream, the name coming from a quote depicting “two people you can’t trust,” Powell says. “We thought that fit fiction writers and poets pretty well.

“It was really cool, but it was awful competition, with 10 literary bookstores in L.A ., all better established than us. We were so broke. It’s not a good town to be broke in.”

Powell says his bookstore dream “only lasted six or seven months, because Lenny (a business partner) tried to kill me.” Powell offers no detail of said attempted murder, which was really extreme exasperation of Powell’s lack of customer service skill, he explains.

“I wasn’t meant to be a clerk. That was the end of my bookstore days. I came back to Indiana.”

Powell says he returned, in part to care for his widowed mother. His grandparents, who lived south of Indianapolis, were aging, too. He stayed with them as he looked for work in Indianapolis.

“Work …as a writer,” he says with a note of sarcasm. “In 1977. There was no work for a writer in Indianapolis in 1977.”

Freedom & Frustration

But there was something called “Free University.” Powell had a cousin, a poet, Tom Hastings, who was teaching poetry classes with the free-wheeling, counter-culture-ish organization born out of the Berkeley free-speech movement, with the motto: “Everyone Teaches, Everyone Learns.”

Classes were either free, or at least, very cheap.

“Free U was a hugely successful thing here in Indianapolis for a few years,” says Powell. But the “organization,” such as it was, was not defined by its intellectual pursuits.

“We had 300 disco-dancing classes a term,” Powell says. “Then, when disco died, aerobics came up.”

Disco and aerobics were blessings disguised in leg warmers for the Free U writers. “They were bringing money in like you can’t even believe,” Powell says. “So, they had plenty of room for free writing classes that made no money at all.”

Hastings taught poetry, while Powell taught fiction. Hastings published a photocopied lit-mag of sorts, called the “Indianapolis Broadsheet,” the only literary publication in Indianapolis at the time, which didn’t last, as “Tom was a poet, not an administrator.”

Hastings moved to Bloomington to teach at an alternative high school, and Powell was left with the Free University literary “stuff.”

Literary life continued to be a challenge in a city addicted to line dancing, group exercise and macramé, Powell says.

Case in point: “There was a reading at the old Hummingbird Café with Robert Bly, Etheridge Knight and a jazz saxophone player from New York. “Eight people showed up,” Powell says. He was astonished, appalled, and distressed.

“I said to myself: ‘I can’t live here.’ ”

There were others in town with similar frustrations.

“Two guys had been running a series at the art museum who had been kicked out because they spilled wine in a grand piano in one of the reception halls,” Powell says. “So that was dying. And, there was an open reading series at a The Broad Ripple Tavern. I was up there with (poet) Alice Friman.

“The reading I went to got cancelled because the owner of the bar said that the time before, plugging the amp in, [someone] had unplugged the freezer and ruined a lot of stuff.”

Powell pauses, smiles. “…I thought he just wanted to get rid of the poets, to be honest with you. So we were sitting around there with nothing to do, and I volunteered to find a new place for the readings.

“…Famous last words!”

Born in the Alley Cat

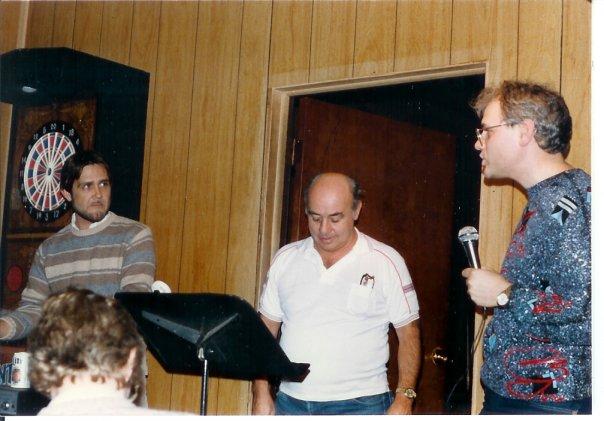

Left to right: Jim Powell, Alley Cat Lounge owner Ray Modlin, and series host

Left to right: Jim Powell, Alley Cat Lounge owner Ray Modlin, and series host

Kevin Corn.

That’s when the Writers Center was conceived. In 1979. In complete frustration; with alcohol as a courage-booster.

Powell says that he knew that the Alley Cat, a “historic” bar he describes as “one of the 10 best dive-bars in the United States,” had two back rooms — one for pool, and one empty— a perfect venue for meetings and readings, he thought.

“I was scared to death, because Ray, the owner back then, was a big, gruff, truck-driver-type guy.”

Powell says he loosened his fear with a few drinks then approached Ray. “I said, ’Ray, wouldn’t you like to have a little poetry reading in here?’” Powell says he was astonished by the reply.

“He said, ‘Really good idea!’” Powell laughs with the memory.

“We were there eight years. Twice a month. So that was the first formal activity of the Writers’ Center. We decided it was an organization. It was the ‘Free University Writers Center.’”

Powell says it was fortunate that the fledgling center, though still connected to Free U, kept its own financial books. Because Free U was in trouble.

“Free U lasted until 1984,” Powell says. “And ended in semi-scandal, after the director, who was a good guy, but he was spending the money like it was his own. By then, aerobics and disco dancing had died. They were failing quickly, and had gone into bankruptcy.”

The writers center had cultivated its own books — and friends. It thus was thrown free of the mothership’s crash.

“A donor came forward with start-up money, and we incorporated in 1984 as the Writers’ Center of Indianapolis.”

The plural-possessive placement of the apostrophe after the ’S’ was very purposeful, Powell says, “because it was owned by the writers. That was the idea. It’s a redundant apostrophe; you don’t need it. (The IWC dropped it a few years ago.) But we were emphatic.”

Imagine it: A group of writers sitting around a table in a smoke-filled bar, drinking and discussing the placement of punctuation. Electric.

“It was very much art for art’s sake,” Powell says with a smile.

“Something was needed, I think. There was nothing else like it around town.” Powell visited more established writing groups, in Washington, D.C. and Minneapolis. “The Loft in Minneapolis was huge. Minneapolis was a place where people did the arts.”

Not so much in Indianapolis, then.

“We were always struggling,” Powell says. “The fiction workshop met right here in this living room, for years.” Powell’s front room is warm, with low lighting and wood floors. Books are placed as though they are being read, or waiting to be.

“We had no headquarters; this was the headquarters,” Powell says. “I always had a full class of about 10 people.” The room in the Broad Ripple bungalow isn’t large; it would certainly be an intimate gathering.

Writing Nomads

As the group grew, Powell says there were other venues for the wandering writers. A printer offered the second floor of his company in Speedway.

“We took it. It smelled like ink. It was bad, and probably contributed to my COPD, when I think about it. But it was space.”

The group was getting grants by then, and the free space was welcome. After that, Marian College housed the center. First, rented space in a dorm, then the caretaker’s cottage, Stokely Mansion, “which was pretty doggone nice,” Powell says.

There was enough room to run one class, a library where there was comfortable seating, an office and kitchen. “We did a lot of events there — some twice a week. More poetry than fiction, for sure.”

It was during that era that the Writers’ Center took over Ball State’s spring poetry festival, which had lost its funding. It started as the Spring Poetry Festival, became the Fall Fiction Festival, and eventually The Gathering of Writers, which today remains the IWC’s signature writing event of the year (March 9 this year at the Indiana State Library).

“We had good turnout right from the beginning,” Powell says. “We could have made money, but we broke even.”

The Writers’ Center revolved around events like The Gathering. “I always thought of it as a political act, too, Powell says, “all of which was supporting writers and the education of writers.

“I believed communication was the bottom-line in politics. If you teach people to be better writers, you get better …everything.”

Being the only writing game in town had its benefits, Powell says. There was little competition for grants. Powell admits, the writers were a bit full of themselves. “If you saw the mission statement, gosh, it was 20 pages long!”

They were also busy, with some ideas that worked, others that didn’t, including “a creative writing road show” where writers went to libraries around the state. “That was great idea that didn’t work very well.”

The Writers’ Center was more successful publishing chapbooks and anthologies, and had a magazine, “INprint, while still affiliated with Free U. (INprint became Flying Island, which is now entirely online.) Powell edited what he calls the center’s “first ‘big’ book” called, New Fiction from Indiana.

Indianapolis Star columnist Dan Carpenter wrote a column about the fiction anthology, Powell says, and sales took off. “All of a sudden, we sold 400 copies of that book!”

Upheaval; renewal

Powell was so busy, he had stopped writing himself. “Writing and editing don’t mix,” he says. And, by the mid-1980s, he was also teaching at IUPUI. And the Writers’ Center paid next to nothing.

“I was being paid very little, and oftentimes, not at all. I got paid one month out of the last 13 months I worked there.”

By the 1990s, Powell felt overworked, underpaid and depressed. “I knew by 1996 that I wasn’t good for the organization and it was killing me, too.”

His personal life was in shambles. A first marriage ended in divorce after just two years, and his mother was beaten when a burglar broke into her house. “I was a wreck,” Powell says.

“We did good work, still. But the organization needed more. I wasn’t the right person to do that.”

Powell says he had spent a good deal of his own money to keep the organization going. “I’m glad I did, but I shouldn’t have. Our board didn’t do their job; I wasn’t getting support. The relationship was severed. It was a sad departure.”

It was 1999. About three others who tried to direct the chaos followed, with varying levels of success. Barb Shoup, an author and former writing teacher, took on the executive director position 2009, a post she holds today.

Shoup gives Powell credit for keeping the organization afloat even during the hard times. “During his 20 years as the center’s director, Jim touched the lives of hundreds of writers, including my own,” says Shoup, who has written more than nine books.

Lists of Writers’ Center-sponsored festivals are replete with notable literary names, including (in no particular order): Susan Neville, Jared Carter, Etheridge Knight, Michael Martone, Alice Friman, Mary Oliver, Tobias Wolff, Andrei Codrescu, Patricia Henley, Scott Russell Sanders, Rita Dove, Dan Wakefield, Yusef Komunyakaa, Haki Madhubuti, Mari Evans, Robert Bly, Denise Levertov….

Powell, who had started teaching part-time at IUPUI in the 1980s, became a full-time instructor. He advised the student magazine, “Genesis,” and it thrived. Now retired, he is a senior lecturer emeritus.

Powell says starting his own writing again coincided with a health scare. He had smoked for 35 years, quitting “not soon enough, believe me. In 2010 they thought they saw spots in my lungs.” It turned out not to be cancer, but the COPD (the ominous acronym stands for “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”) was steadily, stealthily stealing his breath.

Since then, with the help of a creative renewal fellowship from the Arts Council of Indianapolis, Powell has attacked his writing with more urgency — at life-affirming speed.

“I started writing fiction again,” he says with a smile. “And I gotta tell you, it just came; it just flew out of me. Happily, it was much better fiction than I had ever written before, too. Because I knew so much more about it, having taught, and having edited.”

And, at long last, he had figured out the meaning of plot. The late Prof. Vivante would be proud.

“Once I started writing again, I have written pretty consistently,” Powell says. “I have 70-75 stories written to the end. Probably 30 of them edited enough to be published. About 18 of them in this book coming out. One more I’m working on…”

Powell has had stories published in Bartleby Snopes, Crack the Spine, Flying Island and Storyscape, among others.

‘Maddening’ Crowd; Fortunate Friendship

Success isn’t a smooth path. Powell says his stories have been rebuffed plenty of times. He seems to prefer rejection to not having written anything to reject.

Powell smiles through a recitation of recent refusals. “I got a rejection from North American Review today; I got a real encouraging one from somebody last week.” His ego seems beyond bruising.

Powell has many opinions about the way the written word has evolved. Much has changed in the writing world, and Powell realizes he has had a pretty good seat to the evolution.

The future? “I don’t know about the future,” Powell says.

“These hundreds of literary magazines are not going away — well, some of them should. What disappoints me is it is hard for me to find things that have substantial meaning, unless I come back to ‘mainstream’ fiction.”

He names some of his favorites.

“I like Georgia Review, Southern Review, Glimmer Train (which he notes will soon stop publishing). I’m not sure they are being read …by people. It used to be you got published, you were read, you got a book, and you might become famous. That was one out of a hundred people. Now, it’s one out of ten-thousand people.”

Don’t get Powell started on his view of creative non-fiction.

“Creative nonfiction didn’t exist when I was in school. I don’t like it. I don’t like reading it. Most of it would be a better novel. Now it’s acceptable to bend the truth and call it ‘memoir.’ I hate that!”

And, more people have decided they have books living in their heads that they want to extract.

“When I got my MFA, there were 15 programs in the country. There are now 175 residential, and there are 50-75 non-residential, and every little damn college in the world has a creative writing program now.”

Powell doubts the need for so many programs dedicated to mastering writing.

“It’s a shell game. There are a lot of people who write really well out there,” but cleverness seems to win over substance. “Now you’ve got 53-word stories… six-word stories! Micro-fiction! It’s maddening.

“But it is consumable. You consume it and forget it.”

Still, Powell surmises, despite the spun-sugar nature of some contemporary literature, change might be good in the long run. “Literature has changed over time. It keeps changing. What is brought into the canon if you will, will be different, and should be. …And that’s good.”

His view of the Indiana Writers Center — which excised the possessive ’s’ sometime after his exit?

“I am proudest what the Writers Center has done — to try to be more connected to the community; get us out of the ‘art for art’s sake’ mindset” that marked the center’s early years.

Despite his views of the modern writing landscape, Powell, a man who still on occasion instructs young, aspiring authors from an “emeritus” position, has somehow avoided seeming curmudgeonly.

Getting himself back in the writing chair has seems to have been the cure.

Shoup, who took over the Writers Center from a burned-through Powell ten years ago, says his voice has come back strong. Of his story collection, she says: “…each story is filtered through the lens of a writer who knows who he is and where he’s from.

“It has been an honor for me to serve as the executive director of the Indiana Writers Center, where Jim’s legacy is alive and thriving.”

Powell says he looks forward to the launch that has been a lifetime coming. He admits to being nervous; he hopes to summon the stamina to enjoy the limelight. “I look forward to celebrating IWC’s 40th will all the energy I can muster.”

Powell also wishes to share the glow with his wife of ten years, Karen Kovacik, an English professor at IUPUI, a former Indiana poet laureate, whom he lauds for her brilliance as a writer and award-winning translator of contemporary Polish poetry.

To Powell, his wife’s genius extends to her baking prowess, which has added to his waistline, but also her “patience and care,” as his health brings unexpected challenges to their life together.

Another serious influencer in Powell’s life is his next-door neighbor, Dan Wakefield.

Wakefield, novelist, journalist and screenwriter, whose best-selling novels “Going All The Way” and “Starting Over” were produced as feature films, credits Powell with his eventual return to his hometown.

Powell had invited Wakefield back to Indianapolis several times to give workshops for the Writers’ Center. “I was living in Boston at the time,” Wakefield says. He wonders if he would have come back to the place he had not lived since 1950, were it not for Powell’s call.

“He was sort of my re-introduction to the city,” says Wakefield, who moved back to Indiana in 2011. “I have always been very grateful to him for that.”

In a stroke of serendipity, Wakefield became a neighbor when the house next-door to Powell and Kovacik came on the market.

The closeness is more than geographic. “He is a serious writer and a dedicated writer as well as a talented writer, Wakefield says of Powell. “I really admire his dedication and the work he puts in to make his work first-class.

“And, he is a great editor and helped me enormously in things I am working on now.” Wakefield says he has read all of the stories in Powell’s new book. “They are all high-quality.”

A World View, with Endings

Powell says the book is named for one of the stories. “But it also fits my approach to writing and the way I see the world.”

“Ambivalence” has been a regular criticism of his writing, Powell says. That state of mixed-feelings came honestly — out of growing up in a household marked by alcoholism.

“One of the things that gets born in those households is ambivalence. So, the endings of my stories are soft, usually. The change in the characters is subtle,” he says.

“I have always had this problem. I found a note from one of my professors said, ‘You just can’t do it, can you?’” — “It” being, finding a suitable resolution to his stories.

“I can now,” Powell says, with an air of triumph. His stories now have a narrative arc, and, “they do end.”

Even so, he says his world view has changed little. “I don’t have characters having great victories. I occasionally have them having great losses, but usually, it’s softer, you know? They change, but not a lot. It’s the concept of witnessing — of seeing the world.

“A lot of these characters are kind of like me in a way.

“So it’s a witnessing — only.”

Celeste Williams is a journalist and playwright, and is currently the president of the board of directors of the Indiana Writers Center.

_____

More information about the benefit:

Only Witness

A Benefit for the Indiana Writers Center featuring Jim Powell,

with an introduction by Dan Wakefield

Friday, March 8th 6-8 p.m.

Schwitzer Gallery of the Circle City Industrial Complex

1125 Brookside Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46202

$35- individual (includes a copy of Only Witness)

$50- couple (includes 1 copy of Only Witness)

Go here to register for this event.

Left to right: Jim Powell, Alley Cat Lounge owner Ray Modlin, and series host

Left to right: Jim Powell, Alley Cat Lounge owner Ray Modlin, and series host